Lessons from an Avalanche: Humility and Vulnerability - The Risk Manager’s Two Most Useful Tools

“A Stoic is someone who transforms fear into prudence, pain into transformation, mistakes into initiation, and desire into undertaking.”

He was watching me as he heard the snow settle; it is an eerie, hollow bass note associated with the movement of vast amounts of air. I know how disturbing that sound is; it was my cue to frantically assess the situation and try to figure out what to do next. I could not think of him then. He saw the snow start to crack around me, and large blocks slide into the bottomless, flat light. Simultaneously, I felt the pull on my feet; I was fighting to stay above that tugging force while worrying if my left foot was about to be snapped. At that moment, there was no room for me to ponder on what was going on in his mind. The menacing hiss of the white flow of crystals gaining momentum, no doubt impacted him. I focused on fighting my way out to the side.

It was after the exertion of climbing the debris back to him that I got close enough. It was after I had paused to take photos while calming my breathing that I saw his face. It was stoic. I, on the other hand, was feeling quite the opposite. I could not shake the thought of what he would have been feeling if he had had to come down to dig me out. How would the loneliness of the beacon search have scarred him? What would have been going on in his head if there was a ton of snow to shift? Would he have channeled all the experiences we have shared to know what to do without my help? At that moment, I felt my slip/lack of judgment as heavy as the coffin of snow I had just avoided.

We all mess up. The question is, what do we do after making a mistake?

So I want to share why outing myself is such a beneficial process. I want to explain why we need to support this kind of behavior and how that looks. And then I want to tell you what happened up at Jones Pass and what I have learned so that you can contemplate it and hopefully not have to make the same mistake I did.

The first question is, why am I bringing this to you? My ego is going to suffer. My perception of my reputation will struggle. I am opening myself up to criticism and the usual social media berating. Heck, this is an emotional topic; children in the backcountry, some folk feel what I do is approaching evil, and they will be happy to let loose. I get it. I am exposing myself.

Yet, there is so much good that comes from this. Writing helps my self-reflection; it allows me to step aside from the emotional and be pragmatic. I can look at what happened and what led up to it objectively. Over time I will see with more clarity what exactly occurred and what steps were involved. I may even come to a place where I can prevent similar situations from reoccurring because I will have an awareness earlier in the process. Let's be real here. If I do not expose my underbelly; then, I do not get to see it either. I will follow the same habits and internal guidance system that is obviously flawed, or I would not have been in that situation in the first place. The other benefit is that it provides catharsis; I do not wish to keep re-living this particular moment. I want to learn and move on.

Let's take this even further. Over 25 years of working in outdoor education, one place stands out as demonstrating the best example of risk management. They also had the best risk management document and protocols. So what did they do to earn this praise?

Every day the staff met for breakfast (it is a residential center) and then went into a meeting. The mood was always light, supportive, joyful even. After discussing the day to come, if someone had been involved in a near-miss the previous one, they shared it. It was already written up in the near-miss book. If it was the first time for that particular incident, it would initiate a discussion. What had led up to it, did a new protocol need to be created? If the near-miss had happened before, did current protocols need to be discussed and evolved? If there was something that needed amending immediately, it was noted and shared with everyone. Every three months, the whole staff, including part-timers and freelancers, were invited to a risk management meeting; all the near misses and amendments from the previous quarter were discussed. The risk management document was then updated. At no point in this process was anyone berated. Everything was seen as an opportunity for growth and to support those involved. Put simply; it was a kind environment where people not only felt comfortable; they were also happy to come forward and discuss events and what had led to them, even when they saw themselves as being at fault. In turn, this led to exemplary practices that developed continuously.

I share this because I know how productive the process is. I know that we need it to help avoid more accidents and more deaths. I am also contemplating how the current case slated for the court in Colorado has the potential to further undermine behavior. I hope beyond anything that the judge sees how critical the sharing process is, how their judgment will impact it, and then acts accordingly. However, it is not just judicial officials ruling in the case regarding the avalanche above Eisenhower Tunnel who influence these open and productive conversations. We all do. It is hard to put ourselves out there when we know how the armchair critics will respond. In this highly volatile snowpack, we need to know what is going on. The Avalanche Information Centers need to receive reports of any snowpack information to provide accurate and useful forecasts. With so many people coming to the backcountry for the first time, we need to share a real narrative of what can happen or, even better, what is happening so that our new friends can navigate their journeys safely. To help this process, we all need to be kind. We need to refrain from knee-jerk judgment. We need to solicit learning through thoughtful and supportive questions coming from a place of beneficent curiosity. We need to model best practices and, we need to own our mistakes to help prevent others from making them. It is not easy, yet if we are honest with ourselves or free from delusion, then most of us will say, "there but by the grace of (insert a figurehead of your choosing) go I!"

So what happened up at Jones Pass? Well, like all incidents, it was not down to one thing or one decision; it was the culmination of a few.

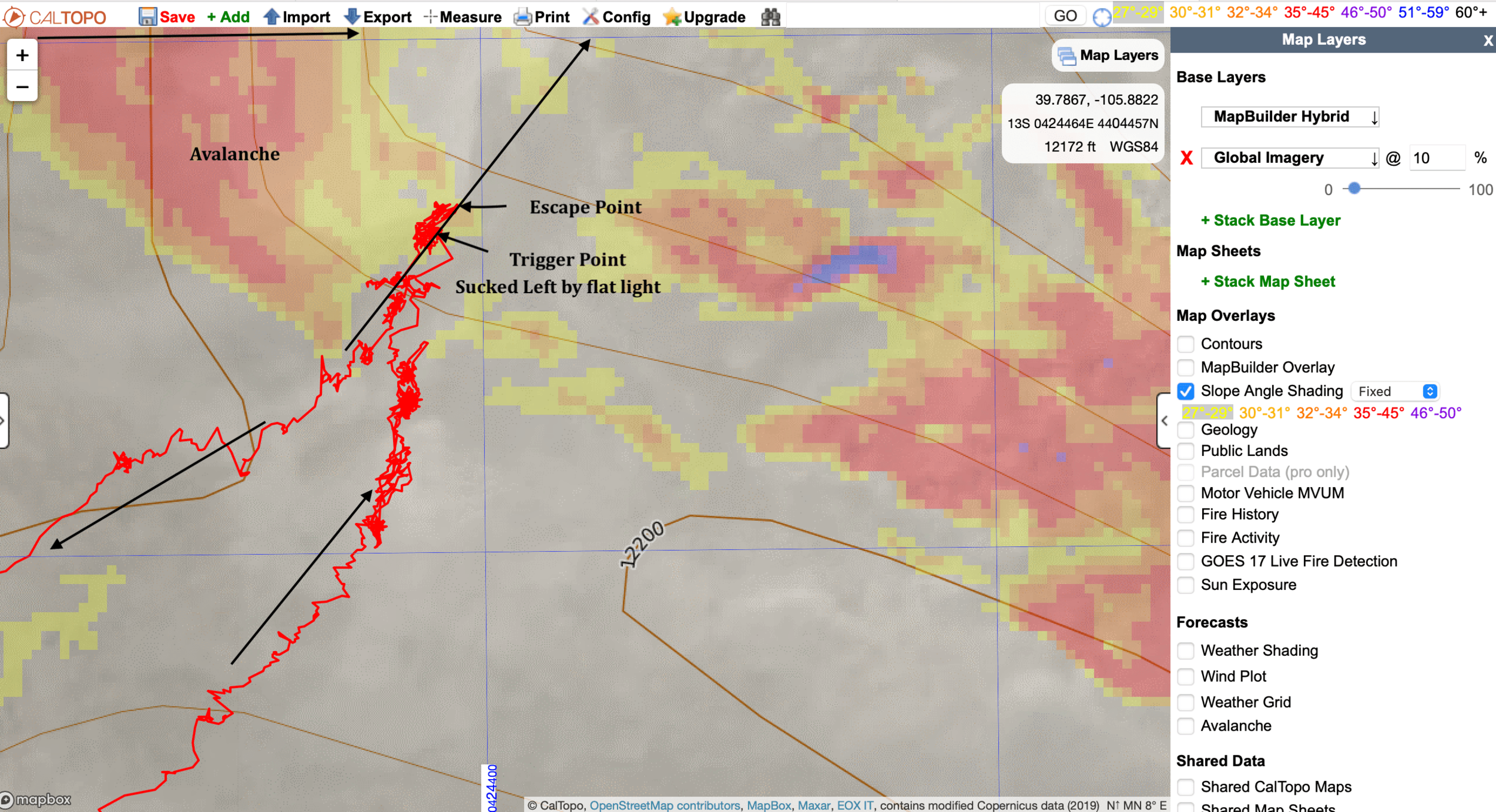

The week before, we had been thinking of places to go. A lot of our early-season, quiet, go-to spots have been found by more people. That is not a bad thing, yet it makes me want to seek out other locations, ones I have not visited. Armed with maps, guidebooks, and the internet, I look for new venues that show promise. I use slope angle shading to find routes that are, for the most part, clear of color. Being that the snowpack is shallow and knowing that the wind had been coming from the west for days, I searched for places that would attract new snow. In other words, Easterly facing slopes that were catching the wind deposits. I also know that these slopes when steep enough, are the ones that will avalanche. When inspecting the map, our route was enticing; it is complex terrain, yet a line led through a short steep section to access more mellow terrain below. We call this threading the needle. Below that, there were going to be several rollovers to negotiate; they looked short. They also appeared as if they were manageable with careful micro terrain selection. The approach to this point while traveling beneath slopes steep enough to slide looked as if it too could be mitigated through strategic route choice and travel techniques. We decided to take a look.

Soon after leaving the road, we knew the pack was tender. We did not have to dig a pit to find that out; the sound of whoomphing as the snowpack collapsed and settled told us all we needed to know. We spread out to travel beneath the steeper slopes that lead to a col. I was confident there was enough gentler terrain between the bottom of the run-out and us to make it a viable option. Again I felt more settles as we progressed but heard nothing fail higher up the slope. We reached the col. Looking down the other side, I waited for Cai to discuss our options.

We looked at the map again. The strip through the middle appeared wide enough to follow. By looking around, it was evident that the snow on our left was steep enough to slide, yet the shape of the terrain suggested that if it did slide, it would funnel into the gully feature. As long as we stayed right of that, we would be golden. My biggest mistake was ignoring the fact that the light was flat. I did not anticipate how I was going to be suckered into skiing in the wrong direction. On my second turn, I went too far left.

I was conscious of the settle, I heard it, and then I felt the snow break up around me and start moving towards the gully. The slope I was on was less than 29º, but I had hit a convexity; I had not seen it, but I felt it and knew I had messed up immediately and started to turn back right. My left foot got caught deep, and thankfully my ski came off; I pushed hard to release from it. Once I got my foot out of the snow, it stopped moving, and my ordeal was over. I collected my ski and then moved over a few steps where the snow was still intact. On looking around, I saw how I had triggered and released the whole slope on the gully's West side. We could not see precisely how far the crown wall reached, but it was undoubtedly 100m. The wall height varied from 20cm to 75cm. A lot of snow had moved down the slope; the flat light meant we could not see exactly how much.

While the snow was still intact to our right, and it would have been feasible to carry on with our initial plan, we were both spooked. There would also be a few more short needles to thread to gain the West Fork of Clear Creek. We decided to retreat the way we had come and enjoy the mellow meadow lap we had skied a few times before. It was fun.

So the mistakes. Firstly, while I thought we were toning it down, we were still in complex terrain. The thing about threading the needle is that everything has to go right. There is no room for any kind of error in this situation. Knowing that the instabilities existed, I had stacked the odds against us. Throw in the flat light, and we had a few reasons to turn back sooner. Having a third person would have encouraged more discussion of our intentions. Another check and balance is a good thing, it is also useful in a rescue scenario. Cai trusts me to get everything right, (expert halo?), hopefully not so much now. I will be working hard to regain that trust though, and in particular, I will be trying to make sure I deserve it.

Remember, it doesn't matter how many times we get it all right, or even how many times we have been lucky. When the house of cards falls, it inevitably lets us know that we have made an error. The reason I am still here is that we got some things right. We read the map and the terrain correctly. Yet, I did not expect snow to move at that low of an angle. Obviously, I was foolish in that assumption. Thankfully it did not move far.

The conditions are incredibly sketchy this early season; they will likely persist well into the spring. I encourage everyone to heed the warning. Keep your angles low. Avoid steep slopes above you, and, unlike me, be wary of steep slopes connected to the side of your route. Meadow skipping can be fun.

Lastly, channel your inner stoic. I intend to use this experience to find more prudence and initiate more thought and study before leaving the house. We will increase our protocols and write more things down. We will make sure to ski with others on our "exciting" tours. Heck, I will probably break down and buy a couple of radios. In the words of the latest Stoic hero, "this is the way."

Looking forward to many more days like these. About to ski Mt Adams, WA. Rainier in the background.