Lessons from an avalanche:

They say smells trigger the strongest memories. What you notice when you trigger an avalanche are the sounds and a feeling of moving air. I have purposefully triggered a number of them. How else do we know what we are dealing with?

Last week on February 20th I witnessed a rather large slide and it sparked a lot of thinking. Firstly, anyone can be caught out. It is over 30 years since I unintentionally caused a slide. Thankfully that time I stepped over the top of it. We had also done a lot of things right this day. I was not even in harm’s way but I was the trigger. The debris did cross our tracks and a friend was caught on the other side of it.

We had looked at the feature and opted to skirt it, avoiding the terrain that we thought could produce an avalanche. The resulting slide was bigger than I anticipated and we obviously did not skirt it enough. If I am honest I did not think it would release. Throughout the day we had spent time contemplating terrain and the probability vs the consequences of avalanches. This had even instigated rerouting our descent. There had been no signs of instability. No collapses. I had cut slopes and maintained escape routes where I was wary. Nada. We were well spaced when we did cross below the eventual slide. The first 2 of us got through.

What I thought might rip out.

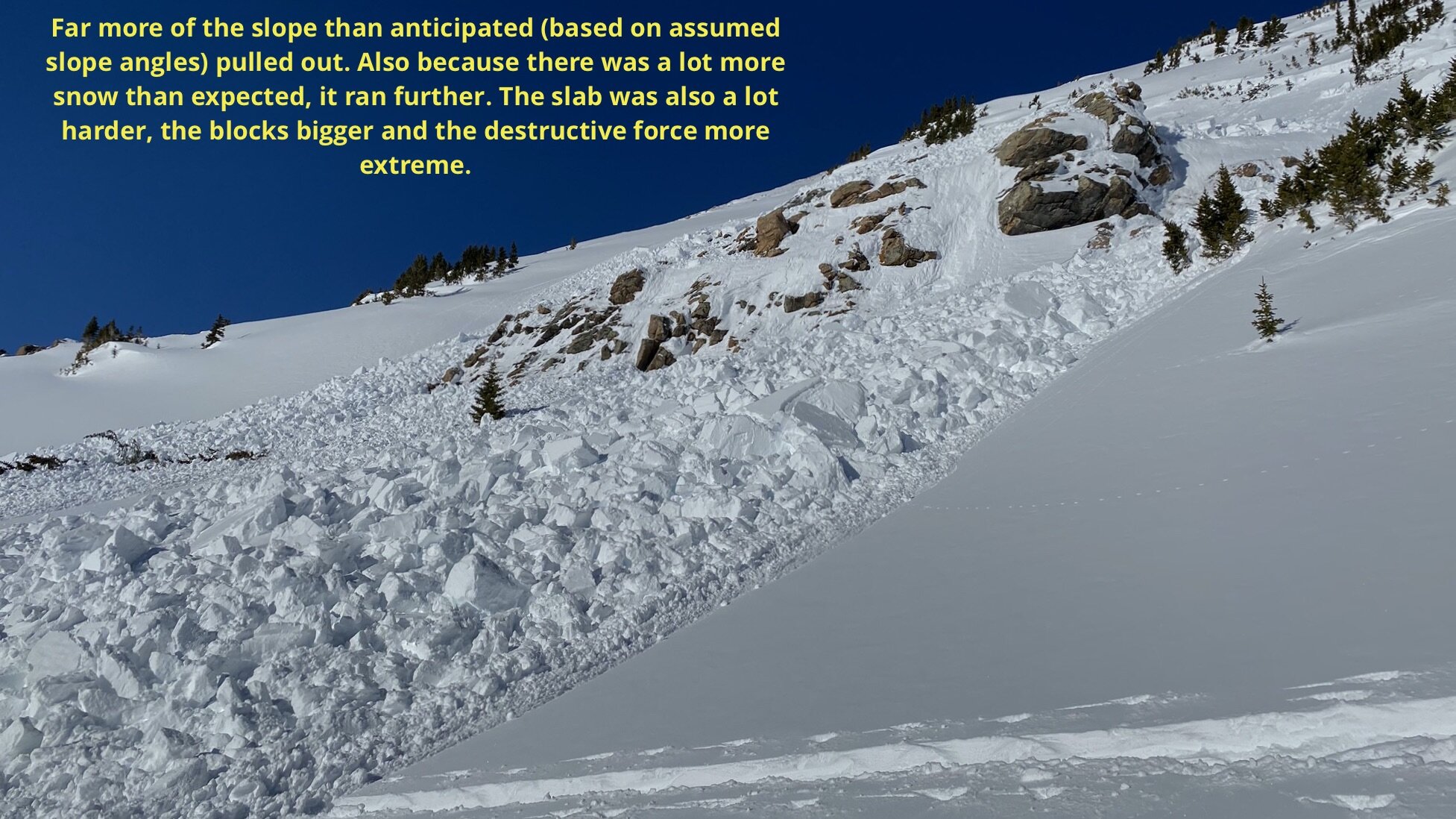

What actually ripped out.

I was the trigger. I struggle with that thought. I do not like to think that I could cause another person harm. I collapsed the pack when turning to look at videoing Michael crossing. The initial collapse was on a small ridge by trees. It was out of harms way of the terrain feature we had identified could funnel snow. It was probably made possible by the warmth of the day heating the tree and its roots. I didn't even believe that the snow I was on was connected to the snow hanging higher up the hill. Most propagations I have seen have traveled in a consistent trajectory. I am guessing that the snow I settled triggered a sympathetic settle below me which then propagated up the slope.

The crown wall was about 200 m wide and was consistently sized (approx 1m high). I think the initial collapse was in the upper, weak layer and it then stepped down. For such a small slope it produced a lot of debris. If we had been caught on the slope (we had no intention of being there) the outcome would have been very different. The slide created a bigger alpha angle than I thought possible and traveled through some low angle terrain.

The big lesson here is to give a wider berth than I thought necessary. This appears to be especially the case because of the rapidly warming temperatures and aspect of the slope. Even though the snow came in waves and was slowing when it reached our tracks, there was so much of it that it pushed on farther. Whether it would have buried someone or even injured them if it had caught them while crossing in our tracks is open to debate but I would not like to try it.

As mentioned, the noise is what sticks with me. Kerstin and I were safe but as soon as I heard the settle I was looking to account for Michael. It was like watching something in slow motion. First, there is the whoomph. There were no obvious propagating cracks or snowpack dropping below the rest. The slide then came in waves pulling out more snow in each pulse. It sounded like a big mountain river trundling rocks along its bed. Most avalanches I have heard have been quieter; silent destruction. It is like when you know there is a venomous snake nearby but you cannot see or hear it. It is a feeling. This guy though was a big roaring giant. Michael was making to move but having a vantage point we could see that he was on an island of safety. The exposed rocks that made the slide possible were also parting the passage of snow into two paths. We called for him to stay put. It would have been terrifying to be in his position. The view above him was obscured but he had a front-row seat to the carnage of large blocks pouring down in front of him and he could hear the trees breaking behind. It would have been an unpleasantly visceral and personal experience.

We were too overwhelmed to stay, look around and glean more information and opted to ski straight out. We did not talk much about it but it was obvious we were in our own private worlds. I have certainly never seen my son’s dog Baggins love on someone outside of his family as he did with Michael. Laying his head on Michael’s lap he obviously understood far more about what Michael was feeling than I did.

So what were the lessons:

No one is immune, we all make mistakes.

Just because you are the trigger does not mean you will be the one caught.

You can do nearly everything right, but the one mistake you make can have harrowing results.

Changing temperatures are worth noting especially around sun collectors and conductors (rocks and trees).

More hasty pits would have provided more information.

Just because it is not likely doesn’t mean it cannot happen. The CAIC website did not tout SW aspects as being problematic that day. Other aspects were highlighted.

No signs does not equate to no danger.

Give loaded slopes a wide berth.

An Addenda from Michael:

When Wil told me he was writing about this experience last week, I asked him if I could contribute to the post. He describes the events as they happened, and our day leading up to it. We had made good choices all day, even choosing to skip a line I really wanted to ski because we decided it wasn’t safe. We’d even stopped to spend some time looking back and talking about why.

As mentioned, Wil has been in the presence of avalanches before, and this was the first one he’s triggered unintentionally in 30 years. However, I had my first backcountry skiing experience with Wil 6 years ago and I finally I took my AIARE 1 course this season. Until now, I’d not experienced anything this closely.

The way that Wil describes the sound, that huge whoomph followed by a river sound is, indeed, what will stick with me. I heard it and looked around thinking “what was that” Things happened quickly, but not so quickly that I couldn’t realize what was going on. It was only seconds after that initial sound that I saw the snow coming towards me. I started to move, but heard Wil call to stay where I was. I did, and I watched.

After it happened I skinned back over to the debris, to briefly check out first hand how huge those blocks of snow were. I imagined what it would be like being under them or digging someone out. This is discussed in a AIARE course, but seeing how firm the snow is when it has settled is itself, unsettling. I realized just how difficult this lifesaving task would be.

Our obs report which was shared and written that day can be found here.

The first part of video posted in the report shows my vantage point from about a minute after the snow stopped sliding. I luckily was in a clear place when it happened, possibly because I was tired and moving slowly after we’d already skinned quite a distance that day. Only a few seconds later and I might have been in a different place. I guess that time I was fortunate to be the slow skier.

For the next few days, I thought I’d be spending time away from the backcountry, staying in the resort. And while I had a blast skiing at Copper and Arapahoe Basin, I found myself back out there again today. In fact, today I was lucky enough to be in similar shoes to Wil that day 6 years ago. I took some of my co-workers and friends on a tour at Berthoud Pass. For some of them, it was their first time backcountry skiing. At the end of our day, a couple of them said it was the best snow they’d ever skied. Awesome. How lucky am I that I’m now sharing those same experiences that Wil did with me years prior?

In reading Wil’s writing, he said that he struggles with the thought that he might cause another person harm. While that certainly must be a challenge to cope with, heading into this terrain, we all need to know the risks. And if anything, he’s helped keep me out of harms way. This is also why I trust him. He’s educated me on much of my backcountry experience, he’s planned routes and helped me make safe decisions for years, including the first day we ever went out in Watrous Gulch.

The lessons that Wil shared are important to keep front of mind. The mountains are unpredictable and we are all responsible for our decisions. I almost made some questionable ones that day, but I’m happy that I was with my friends to counter and question them. While our group caused a slide, we did a lot to avoid it.

More than any AIARE course, I’d suggest you find a mentor, a friend that you trust to help you in the backcountry. Someone that won’t bail when you need them. Someone that will be encouraging when you need them to be, when you think you can’t go farther, but you can. Being out with people you trust is perhaps the most valuable resource you can have in the backcountry. And, getting to share those experiences with others is perhaps the best part.

Our route up the West Fork of Clear Creek near Jones Pass. CalTopo.com